Mastering slow flight

Slow flight is a skill that a lot of people don't think much about and regard only as a box to tick on a checkride. Having a solid grasp of the aerodynamics of slow flight and some techniques to perform it while being evaluated should help make it an easy pass task next time you get evaluated.

Aerodynamics of slow flight

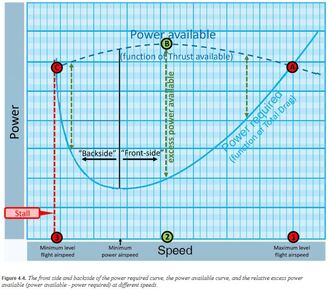

AFH Chart from Chapter 4

AFH Chart from Chapter 4

When flying slowly, there are a handful of things that will work differently. Most of these are covered in energy management or the PHAK. Some key highlights to keep in mind:

All of these factors mean you should spend time flying the airplane as slowly as you can. Practice slow flying as slowly as you can, with the stall horn singing loudly, to get as comfortable as possible with it. Play with the energy lever: give it brisk adjustments and then try to adjust your energy distributor to hold airspeed. It's hard, isn't it? Now do it more gradually to see how much easier it gets. Explore the slow corner of the envelope thoroughly before focusing on how to do it in a graded environment.

- Kinetic energy scales quadratically with speed (KE=1/2mv^2), so you have 1/4 the energy at 50 knots that you did at 100. You don't have as much to trade if you need it.

- Lift scales quadratically with speed. This means your control inputs (which alter CL) become less effective with the same relationship (colloquially "mushy controls").

- Induced drag scales as the inverse square of speed. This has two important consequences:

- A required control throw made to fix an error will cause more drag at slow speed.

- Total drag will be higher at slow speed, so you will be in an unstable power-drag equilibrium (position C at right). In a perfect world, you'll want to sneak away from this spot.

- Turn rates will be faster and radii will be smaller for a given bank angle at slow speed. This means you should plan shallow bank angles because a) turns will happen faster and b) you don't have much energy to play with.

All of these factors mean you should spend time flying the airplane as slowly as you can. Practice slow flying as slowly as you can, with the stall horn singing loudly, to get as comfortable as possible with it. Play with the energy lever: give it brisk adjustments and then try to adjust your energy distributor to hold airspeed. It's hard, isn't it? Now do it more gradually to see how much easier it gets. Explore the slow corner of the envelope thoroughly before focusing on how to do it in a graded environment.

Slow Flight as a graded maneuver

Once you've thoroughly explored the skill set of flying slowly and are ready to practice it as a graded exercise, you can use the below techniques to make life easier:

Find the horn: the ACS tells us to pick a speed where if you go any slower, it will provoke a stall indication. We know from the aerodynamics of slow flight that the slower you go, the harder it gets to control airspeed. Within reason, you should try to find the fastest speed at which the horn comes on, and then give yourself a small additive of 2-3 knots to set the left side of your energy box. If your evaluator lets you pick a speed, go as far to the right of your total drag curve that you can get away with. (Hopefully you don't all go hunting for the plane in your school's fleet with the chirpiest horn for checkride day....)

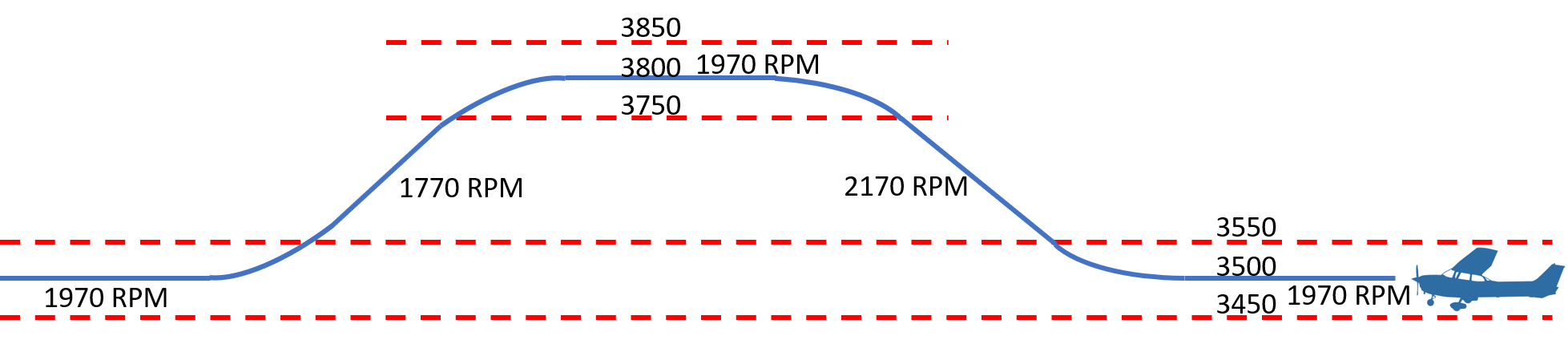

Know the box: slow flight the ultimate test of whether you understand how to stay in the energy box. For the Commercial rating, you get +5, -0 on speed and ±50 on altitude. That's a tiny box. I like to stay +3 in that box, because it's close to the middle, and it's further away from the unstable equilibrium. In a 172, an RPM of 1970 is typically about the right starting number for straight-and-level.

Know what's not in the box: there are two very important variables that are not prescribed, so you should make full use of these:

Don't call "established" until you truly are: spend all the time you need to set up on altitude and airspeed. Note your RPM before you call established, that will be your new zero point.

Climbs and Descents: Most evaluators will ask you to climb and descend to a new altitude. Here's where I've seen most busts happen on this maneuver. Someone either crams the energy lever in or yanks it back and promptly exits the energy box. This part of the exercise is where you need to take full advantage of the lack of a time box. Let's say you're at 3500 feet and you get asked to climb to 3800. Before you do anything, check your energy input (let's say it's still at 1970). Next, gradually add energy while directing it upward and adding a toe of right rudder to handle the added slipstream and P-factor. In a 172, the added propwash will make the nose want to rise and slow due to the power-trim couple, so anticipate that and add some forward pressure and trim if needed. Spend maybe 10-20 seconds gradually walking your energy lever up to about +200 RPM from where you started. Once you've established a solid climb, stop messing with it. As you get to the -50 floor of your new energy box (3750), gradually start easing back on your energy lever so that your climb rate tapers off to zero as you converge on 3800 at your original setting (1970). You don't want to hit your target, you want to converge on it. Descents make use of the same philosophy: gradually ease your energy lever about 200 RPM back over 10-20 seconds, let a slight descent start with a bit of nose-up to counteract the power-trim moment, then begin your new altitude intercept at the +50 ceiling of the energy box and converge, again taking 10-20 seconds. If you catch yourself leveling early, you can always hold whichever instataneous input you have for a bit longer to let it settle closer to target. Every student I've shown this technique to can hold their airspeed ±1 knot. All it requires is patience, planning, and knowledge. If you slow fly slowly, it will be so much easier, so you won't have to practice as much to make perfect.

Find the horn: the ACS tells us to pick a speed where if you go any slower, it will provoke a stall indication. We know from the aerodynamics of slow flight that the slower you go, the harder it gets to control airspeed. Within reason, you should try to find the fastest speed at which the horn comes on, and then give yourself a small additive of 2-3 knots to set the left side of your energy box. If your evaluator lets you pick a speed, go as far to the right of your total drag curve that you can get away with. (Hopefully you don't all go hunting for the plane in your school's fleet with the chirpiest horn for checkride day....)

Know the box: slow flight the ultimate test of whether you understand how to stay in the energy box. For the Commercial rating, you get +5, -0 on speed and ±50 on altitude. That's a tiny box. I like to stay +3 in that box, because it's close to the middle, and it's further away from the unstable equilibrium. In a 172, an RPM of 1970 is typically about the right starting number for straight-and-level.

Know what's not in the box: there are two very important variables that are not prescribed, so you should make full use of these:

- Time: there's no time limit! Don't let yourself or any evaluator rush you through this. Fly slow flight slowly!

- Bank angle: also no prescription. We know from our aerodynamics above that we turn faster, experience more adverse yaw, and have less energy to play with. This means that your turns should use maybe 5 degrees, 10 tops, of bank. Why work harder when you can work smarter?

Don't call "established" until you truly are: spend all the time you need to set up on altitude and airspeed. Note your RPM before you call established, that will be your new zero point.

Climbs and Descents: Most evaluators will ask you to climb and descend to a new altitude. Here's where I've seen most busts happen on this maneuver. Someone either crams the energy lever in or yanks it back and promptly exits the energy box. This part of the exercise is where you need to take full advantage of the lack of a time box. Let's say you're at 3500 feet and you get asked to climb to 3800. Before you do anything, check your energy input (let's say it's still at 1970). Next, gradually add energy while directing it upward and adding a toe of right rudder to handle the added slipstream and P-factor. In a 172, the added propwash will make the nose want to rise and slow due to the power-trim couple, so anticipate that and add some forward pressure and trim if needed. Spend maybe 10-20 seconds gradually walking your energy lever up to about +200 RPM from where you started. Once you've established a solid climb, stop messing with it. As you get to the -50 floor of your new energy box (3750), gradually start easing back on your energy lever so that your climb rate tapers off to zero as you converge on 3800 at your original setting (1970). You don't want to hit your target, you want to converge on it. Descents make use of the same philosophy: gradually ease your energy lever about 200 RPM back over 10-20 seconds, let a slight descent start with a bit of nose-up to counteract the power-trim moment, then begin your new altitude intercept at the +50 ceiling of the energy box and converge, again taking 10-20 seconds. If you catch yourself leveling early, you can always hold whichever instataneous input you have for a bit longer to let it settle closer to target. Every student I've shown this technique to can hold their airspeed ±1 knot. All it requires is patience, planning, and knowledge. If you slow fly slowly, it will be so much easier, so you won't have to practice as much to make perfect.

Slow flight in a Seminole is even easier because the T-Tail and counter-rotating props eliminate the power-trim couple and LTT that the 172 has, and the thrust line of the engines is close to the vertical CG, so you only have a speed-trim couple. Simply set up at ~18 MP and Full Prop, then gradually walk your torque levers up or back 2 MP for the climbs and descents. It will need a soft nudge on the energy director to direct the added or removed energy towards altitude instead of speed, but will then hold that speed exactly.

Conclusion

A little bit of knowledge and planning can make slow flight a straightforwardly successful maneuver in an evaluation event. Take full advantage of the variables not specified so that you stay in the energy box. As you gain proficiency, you can pick up the pace somewhat, but remember that the energy box is the most important criterion. I once had a fellow stage check instructor tell me "Merlin, your student took forever in slow flight." My response was "Good for him, I bet he didn't bust his energy box." "Fair enough, he was dead on airspeed the whole time."