|

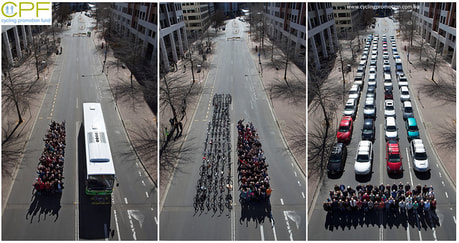

City driving is awful, we’re failing at our emissions and vision zero goals, and outside of more working from home, we have not made much progress on these fronts. Fortunately, these issues are all fixable with small vehicles like e-bikes, scooters, and microcars, as well as a few thousand gallons of paint. Embracing the micromobility revolution will eliminate gridlock, reduce emissions, clear the air, and lower taxes. Where we are today Driving in the city sucks. Highways in major US cities are packed, so you’re often stuck in stop-and-go traffic averaging 20 MPH. On city streets it gets even worse: whenever you’re in a single-lane line of cars 5 deep at a red light, you’ve got a good chance that at least one of them will do a stoplight space out, box everyone out as they attempt to make a left, or box everyone out while waiting for pedestrians to mosey across the intersection when they want to go right. Any of these situations will likely cause you to miss a phase, so you’re stuck waiting for another minute, and your average speed declines. These bottlenecks are a large part of the reason it takes forever to get anywhere in a city by car. When you get close to your destination, you then have the joy of circling the block 5 times to find a parking spot, and your inner monologue goes like this: “Is that a… oh no, fire hydrant, dammit. How about right there behind the… nope, 30-minute delivery slot. Ok, let’s go down this street here. ‘No parking within 30 feet??’ Dammit. ‘Street cleaning Tuesdays.’ Today’s…wait, oh dammit, Tuesday.” You continue this game for maybe 10 minutes until you finally find something, then have to backtrack the 5 blocks to get to your destination. By this point, you’re late, frazzled, and your meeting doesn’t go well. These are but a few examples of the frustrations of city driving. In many cities, car traffic moves below 10 MPH. In New York City, it’s around 5 MPH. Commuters in many cities spend countless hours a year sitting in traffic. The bottom line is that cars in dense and congested cities are a slow way to get from A to B. It doesn’t need to be this way. The basic problem: packaging efficiency  You ever order something online like a USB stick, only to have a shoe box-sized package show up with a bajillion packing peanuts and then a little baggie with the USB stick in it? For urban transportation of 1-2 people, cars are the proverbial shoe box for a USB stick: they’re a much larger container than is needed for the payload and mission. This photo illustrates the problem well, with 60 people alternately in cars, a bus, and on bikes: Why do cars have such bad packaging efficiency? Most cars are overbuilt for urban transportation. They’re designed with ranges of hundreds of miles for speeds in excess of 100 MPH, and with safety equipment to make collisions at higher speeds survivable for their occupants. This makes them great at moving payloads around rural and less-densely populated suburban areas, but too large for cities. For urban use, these capabilities add unnecessary weight, complexity, and thus cost to the finished product. The second reason cars are too big is a range of subsidies for roads and parking that lower the direct costs of car usage while driving up costs elsewhere in the economy. Road subsidies artificially cheapen driving According to the Tax Foundation, the share of road funding across the United States from tolls, fuel taxes, and fees lies between 7% and 73%, with a 53% nationwide average. In other words, about half of road funding is subsidized by money from the general tax base. In my city, Seattle, we’ve got the West Seattle Bridge fix/replacement story, which looks likely to cost around $400 million, likely more by the time all the dust settles. We recently spent $3.3 billion on the SR 99 tunnel, a third of which came from state, federal, or local budgets. Many areas also have requirements for “free” parking, which according to Don Shoup is anything but: someone is still paying to provision the space to store the vehicle, in the form of more expensive products, rents, or spending tax money to store private property on public land. In sum, we’re spending huge amounts of public funds on infrastructure to move and store vehicles that are way larger than they need to be, and even then, the user experience is an awful crawl through gridlock and pollution. We can, and should, do better, by right-sizing vehicles for the mission and adapting roads to meet them. right-sizing Vehicles All good engineering projects start with a clear understanding of the problem. According to Table 6b of the USDOT’s 2017 NHTS, average trips are 10.5 miles all-up, and 12.8 miles for commutes. 76% commute alone, though this rate is lower in many cities. The NHTS puts the total car occupancy for all trips at 1.55 in 2009. Pulling these together gives us a handful of requirements for a commuting vehicle:

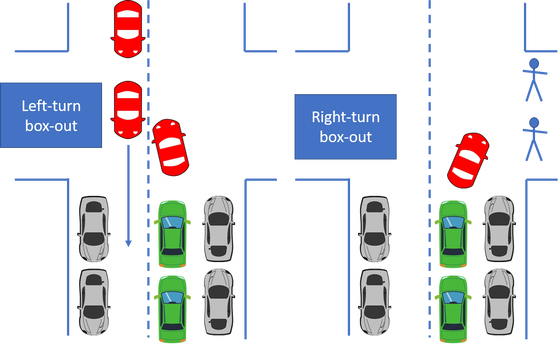

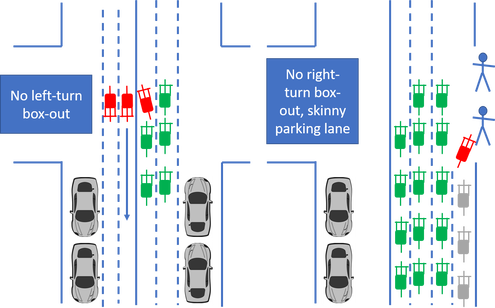

As e-bike adoption increases, we’ll need to focus more on right-sizing roads to accommodate the changed blend of vehicles. Right-sizing roads: lane doubling One major adoption hurdle with e-bikes and smaller micromobility vehicles like scooters and powered skateboards in general is safety. Many people I’ve spoken with about cycling or e-biking in cities are nervous about getting hit, and even confident riders avoid certain areas they deem dangerous. I’ve written in the past that city planning employees should use the infrastructure they’re responsible for building and maintaining, which in places where implemented should accelerate the pace at which problems get resolved. One cheap and elegant solution to increase safety as well as to accommodate a growing number of e-bikes is lane doubling: cities should take a 10-foot-wide lane and paint a centerline stripe down it to make two smaller micromobility lanes for the growing number of small vehicles. Such a change will immediately double the throughput by allowing e-bikes to go two-abreast. Bottlenecks, like the frustrating left- and right-turn box outs will now be cleared: Signal phases can be made shorter because each column of vehicles will be shorter by at least half, further increasing average speeds. In streets where there are two travel lanes and two parking lanes for a total of 4x10’, these can be redrawn to 8x5’, with e-bike/micromobility parking on the sides. Shrinking the width of the parking lanes would allow a third travel lane each way, which combined with the flow efficiencies would yield in excess of a 3x improvement in total throughput. Some lanes will still need to remain wider, for buses, trucks, and other vehicles. Overall, lane doubling and intersection enhancements will allow a combination of increased urban densification and lower road spending. Wherever the throughput requirements can be met with narrower roads and bridges, we can spend less on construction and maintenance and in turn avoid many of the costly boondoggles like the SR 99 tunnel, West Seattle Bridge fiasco, and further examples in other cities. The billions saved in Seattle alone can be returned to taxpayers or reinvested in solving other problems like housing affordability. Smaller parking requirements will mean business owners won’t need to spend as much on that space, which will lead to lower prices for goods and services. Less traffic, cleaner air, lower prices, and less tax: let’s sign up for the micromobility revolution. Implementation hurdles There may be a few of you who are not 100% sold on the urban micromobility utopia (shall we call it “umu?” Maybe not, this is why I don’t get invited to Marketing meetings…). As I’ve developed this idea, I’ve encountered a few objections that I’ve listed below, and several of you will come up with more. When formulating the objections, please consider the following question: “Does the cost of addressing [objection] make the entire idea bad on net, or is it a solvable problem that will eat up a small fraction of the billions in savings?”

0 Comments

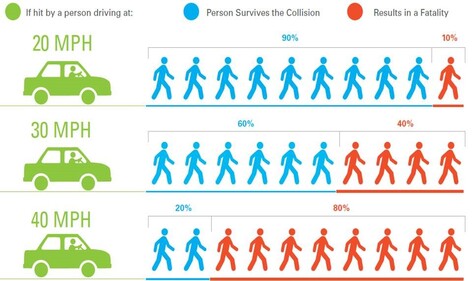

Have you ever gone through a city and asked yourself “Who the hell designed this, and what were they thinking??” I have this thought all the time while cycling around the Seattle area, and often can’t help wondering, “Has anybody involved in planning or building bike infrastructure ever actually ridden a bike on said infrastructure?” The answer in many cases must either be “No” or “They must have a death wish.” Look at this gem: The bike lane goes all the way up to the light and has two bikes stenciled onto it, which clearly means they intend cyclists to be there. On the opposite side of the intersection, there’s an ambiguous shoulder lane that just sort of tapers off on a 6% climb. Meanwhile, the speed limit sign in the distance reads 35 MPH (56 km/h), which means that people in cars are likely going at least 40 MPH (64 km/h). A moderately healthy cyclist climbs a grade like that around 10 MPH (16 km/h), which means the closing speed between car and bike are around 30 MPH (48 km/h) as the cyclist is unceremoniously forced into the “general purpose” lane where most motorists are not looking for them. This is a recipe for disaster, as getting run over at that speed is usually fatal, as seen in several studies and infographics: Vehicular energy goes up as the square of the speed, so anybody on foot, on a bike, or in a wheelchair will have bad chances in such a collision. This makes you wonder what the discussion in the traffic planning department actually looked like when they designed this mess. “Say, Randy, what should we do about the bike lane on the other side of that intersection? Should we continue it?” “Don’t know, Craig. The bridge tapers ahead, so we got a constraint, maybe the cyclists will just levitate to the other side of it.” “Brilliant, why didn’t I think of that? I was thinking of making trade-offs like merging the GP lanes to keep the bike lane, but levitation is much better.” “Yeah, we’ll save half a bucket of paint and a few posts by not restriping that. Sure a few cyclists unpracticed in levitation might get flattened, but the EMTs need practice using their spatulas to clean them up.” “Sweet, let’s go to happy hour.” The reason we end up with such bad infrastructure is that Randy and Craig don’t have a reason to care about what they’re doing. To be fair, they likely face a thicket of red tape and competing departments that won’t give them half a bucket of paint and a night to slap it on the road. Maybe the cone-laying union is on strike as well, who knows. How do we fix this? The solution to shoddy infrastructure is for cities to start dogfooding it: if Randy and Craig experienced the terror of merging their bikes in car traffic on that climb, they’d figure out a better solution faster. On their other rides around town, they’d start finding all the other death traps, like bike lanes in the door zone, tram tracks, and bomb-crater sized potholes on neighborhood greenways. They might look at their city’s budget and conclude that the Vision Zero project allocates more coin to its website than real improvements. In many of these situations, it’s more of a priorities problem than a money problem. Within the first few weeks of the dogfooding initiative, Randy and Craig would experience firsthand where the most urgent problems are, and then work out how to address them. They might have a bit of a budget for speed bumps and signs on a neighborhood greenway, but, having ridden on it, decide that they should skip the signs in favor of spending that money on filling the bomb craters because that’s a greater help to making it safe and usable within their budget. They could likewise use budgets more prudently by alpha testing ideas with temporary solutions like toilet plungers and biodegradable paint, then getting a group of beta testers from the local community to play with it and provide real user feedback, instead of wasting millions on yet another ineffective design. Infrastructure issues are not exclusive to cycling, though that’s where I personally see it the most. Sidewalks could be made a lot more useful with dogfooding as well. Here’s a wonderful specimen of a root bulge in a sidewalk: The ADA spec calls for an 8.33% gradient for curb cuts for navigability, presumably because anything steeper is hard or impossible to climb. This bulge looks a wee bit steeper than that, not to mention the lateral unevenness. If Wilma’s in charge of sidewalks and is required to dogfood it in a wheelchair, this would become a higher priority. She might see the well-paved strip on the other side of the green and ask these types of questions:

Through dogfooding, infrastructure teams will form better empathy for vulnerable road users, and will become better internal change agents. If those they report to remain unconvinced of the new proposals, they should implement “Skeptics Day,” where the dogfooders can invite any city leader for a day out on the “need fixing” roads or sidewalks. If higher ups experience the misery themselves with the cameras rolling, it will be harder for them to retreat into their offices and ignore the problem. If they do try to duck their responsibilities, maybe Randy, Craig, and Wilma could make a solid case for that person's salary to be reallocated to something useful. Where do we go next? The examples here are Seattle-centric, but the problems and lessons apply to plenty of other places as well. If you want to introduce this in your area, get involved with your local cycling/walking/wheelchair advocacy groups, see what they’re doing, and pitch the idea of putting infrastructure dogfooding on an initiative in a local election. Voters across the political spectrum in many places think that infrastructure is shoddy, so the idea of focusing their city’s attention and having their leaders put skin in the game should be broadly appealing. If you’re in infrastructure planning and want ideas on where to find high-ROI areas to address, check out the Strava Global Heatmap for pointers on where heavy bike and foot traffic are, then do a segment search on keywords like “death trap” and overlay those with the high traffic areas to find some areas to put near the top of your list. Lastly, form a user group of locals to give feedback. The fact that someone will finally listen and commit to doing anything should energize locals to provide more than enough actionable feedback.

The CDC tells us to get 150 minutes of cardio a week, yet 3 in every 4 people in the US don’t. Meanwhile, we average 3 hours a day watching TV. Human history is littered with laziness-enabling inventions like the TV remote, created to spare us the suffering of walking 10 feet to change the channel. Zenith even named an early version “Lazy Bones.” I think they were on to something there. The bottom line is that we’re lazy and we know it’s bad for us. Most of the health advice out there is about what to do, but there’s very little focus on how to implement it. I want to offer a few ideas for the difficult part: committing to doing something and strapping on your proverbial gym shoes. Step 1: Figure out your own psychology It’s hard to figure out how best to address something if you don’t fully understand it, so the best advice is to do a comprehensive study of yourself. Here are a few questions that may help you organize your thinking:

Define some internal concept of motivation I think about my motivation like a point system (henceforth motivation points, or MPs): certain things add to the stash, and others deplete it. Most people you see packing the gyms in January are gone in a month because they’ve exhausted their MPs. Define a concept that works for you, and be judicious about how you use your motivation to get out and exercise. Will you be the 0500 jogger? Me neither. Step 2: Find ways to get out the door using what you learned in step 1 and any combination of the below (several are inter-related) Focus on activities you enjoy Several roads lead to Rome, so find the one that gets you there with the lowest MP cost. I don’t like jogging, it bores me to tears. I do enjoy cycling, because there’s more scenery, it’s more cerebral, and I just like it. Find what you like, try a few different things, and then avoid the more boring ones. Schedule in your exercise Some people are very calendar-oriented, so if they get a reminder for something, they just do it. My mom seems to be great at doing this, but I apparently missed that gene. If calendars are your thing, pick a time to exercise, block it out, and then go do it. One advantage that scheduling has is that it makes it easier to keep that time: if someone else asks “Are you free at [gym time],” it’s easier to tell them “Nope, that’s gym time, but I can do [free time].” Exercise to get places Exercising can become a chore, especially if there’s no objective. I ride my bike most places I go, so for me it’s less of a chore to exercise than it is simply a matter of “I want to go to the store/happy hour/friend’s house.” The destination is a great carrot to build the MPs and get going. Pretty quickly, you’ll think of “active transportation” simply as “transportation.” Get your ego into it As we saw in the intro, the idea of “exercise because it’s good for you” doesn’t work for most of us. Does the idea of “do something that your friend didn’t think you’re capable of” get you fired up? If so, goad a friend into betting against you. One time a buddy bet me a bottle of whisky that I couldn’t finish a 100-mile bike ride before lunch the next day. That got me fired up to do it, and the whisky tasted great! Box yourself in The fewer options you have to retreat away from exercising, the more likely you’ll be to exercise, and the fewer MPs you’ll consume in the process. Find ways to engineer your environment to support your exercise goals, both to get you going as well as to keep you going. Hide your TV remote under your gym shoes. Run around a lake or do an out-and-back, because if you lose interest halfway through, you’re committed to continuing one way or the other because you have to get home (at a track, you can bail whenever you like). At several of the places I’ve worked parking passes were expensive, so instead I opted against buying one and decided to ride my bike to work. There are plenty of winter mornings when I wake up, look out at the drizzle, and think “Aw, not todaaaaaay,” but not riding means either $20 in day parking or riding the bus and missing my first meeting. On the way home, the thought process is even simpler: “If you want to get home, you can either ride your bike… or ride your bike!” Also, my colleagues know me as the nutcase who rides his bike rain or shine, so I know that they’ll ask me what’s wrong if I don’t ride, and my ego doesn’t want to have to field that question. Have a gym buddy If you and a friend are both looking to exercise more, try teaming up and keeping each other honest. Book a time, ideally with a recurrence pattern, and commit to holding each other’s feet to the fire. Now if I bail, I’m letting my buddy down. One thing to consider is asking your gym buddy to support you in a way that works: do you prefer them to have a more upbeat “you can do this” attitude, or a sterner “dammit, focus and DO IT” attitude? I personally prefer a harsh Gunny Hartman approach where my gym buddies give me a hard time when I slack off. It may seem weird to be stern with people, that’s why it’s important to articulate when to apply it, e.g. “I’m shooting for 7 reps at this weight, yell at me if I slack or look like I’m sandbagging at 7.” That empowers your friends to lean into you a bit and give you a good ribbing within parameters you’re comfortable with. Compete with others who are out there If you’re competitive, convince yourself that every other jogger/cyclist/walker/lifter/yogi etc. is duking it out with you and that it’s an imperative to win by whichever metric you’ve defined. There’s an entire subculture of cat 6 racing among bike commuters, and I’m sure joggers and others have their own lingo for the concept. This will push you to get you a better workout and make it more engaging than simply going out for a jog/ride/walk. Compete with yourself Set a goal or find an external challenge that provides a north star to keep you on track. This could be anything from “go run a 5k” to “cut my commute time by 5% over the summer.” Be creative, define it, and then find a way to hold yourself accountable, maybe with a tracker, gym buddy, etc. Get addicted to apps like Strava Strava has several functions that can help motivate you: setting targets, monthly challenges, comparing your speeds with others on the same segments, tracking your own personal records, and having a network of friends that you can use for motivation. Getting addicted to some combination of these features can motivate you to go out more, push yourself harder, and find like-minded people to exercise with. Let your freak flag fly Whatever works for you will probably be completely alien to someone else, and that’s totally fine. Some of you probably read some of my examples and now think I have a few screws loose, and that’s totally OK. Whatever you do, don’t let other people’s ideas get in the way of you doing what works best for you. In conclusion… Hopefully some of these ideas will help you get on your proverbial gym shoes and go out there, or inspire you to think of related ideas. Whatever works, give it a whirl, have fun, and embrace who you are in the process. Speaking of exercising, Strava tells me I’m a bit behind my pacing on my annual goal, so I should probably stop typing and hop on my bike….

Originally published on February 8th, 2020

Dear airlines, please sell us sustainable aviation fuels (SAF). It’s the only feasible way to green up aviation at the moment.* I’ve cleaned up most of my CO2-emitting activities, but now flying remains as the largest remaining slice of the pie. I have a family that is spread out over multiple continents and travel a decent amount for work, which usually involves flying. I’m not the only one in this situation: several others have simply decided to stop flying or shame those who do. I’m a strong believer that aviation is good for modern society: about a third of global trade by value is transported by air, and traveling to other places makes us more open and creative. As Mark Twain famously stated, “Travel is fatal to prejudice, bigotry, and narrow-mindedness.” With that said, I’d like to work with you to make aviation a better global citizen as we move into the next decade. How should airlines address this? What I’d like all of you to do is add an option in your booking flow to “fly my seat with sustainable fuel.” You’re clearly experts at upselling exit rows, early boarding, bags, and other things, so I know that building the web experience should be trivially simple for you. From a pricing standpoint, you can compute the marginal cost differential between SAF and fossil jet based on the route, the aircraft assigned, and historical fuel burn to spit out a number. Then we, the consumers, can simply select the option and be on our way. Microsoft has pledged to remove its historical CO2 and go CO2-neutral by 2030, so selling them the option should be a slam-dunk (Delta and Alaska, I’m looking at your corporate contract teams right now) (Edit: looks like KLM has part of the pie). More will surely follow. Some of you have already gotten started in the space, but if I didn’t proactively search for these resources, I wouldn’t find them. If the emergence of flygskam in 2019 is an indicator for the future, then you need to start skating to where the puck’s going by adding the SAF booking option for us. That cash flow will boost SAF investment to accelerate the closing of the cost gap to fossil jet. The IPCC tells us that we’ve got 10 years, so get to work. *Why is SAF currently the only real option? Right now, commercial aviation represents roughly 2% of global CO2 output, and that fraction is climbing. Aircraft efficiency has improved in leaps and bounds during the jet age and continues to improve about 10–15% with every new generation of airliners. These improvements in efficiency make it so much cheaper for people to fly that we are seeing overall passenger numbers climbing at 5% per annum while total emissions are climbing at 3%. By 2050, emissions are expected to be at triple their current amount. What we need is not just to reduce unit emissions (efficiency), but total emissions as well, and quickly. Global agreements to limit emissions have not gone well, as evidenced by the squabbling over the ETS and the fizzled COP 25 summit. Most people think their governments are dysfunctional, so those waiting for a few hundred of those to cooperate must have a lifetime supply of popcorn. What can be done to reduce emissions? Several ideas have been proposed over the years to address aviation’s growing CO2 emissions. Pioneers in electric propulsion like Harbour Air have flown an e-Beaver using a magni-X motor, which will help improve air quality, reduce noise, and reduce maintenance costs. The problem with electric propulsion remains energy density: lithium-ion batteries have 2% the energy per unit weight as jet fuel. Factoring in better powertrain efficiency gets us closer to 7%. I’m excited to see the batteries improve, but it will likely be decades until a battery-powered plane can cross oceans with a useful payload at a reasonable cost. For longer distances, hydrocarbons are presently the only realistic energy source that can keep planes in the air. CO2 offsets have been proposed as a solution, but many of them have their own problems: dig up fossil fuels from long-term storage, introduce it to the short-term carbon cycle by flying, and pay someone to plant a few trees to offset that. Seems great, but how can anyone be sure that those trees don’t get chopped down for firewood in a decade? This leaves us with SAF as our only realistic option. Broadly speaking, SAF includes synthetic fuels made from renewable energy and second-generation biofuels that don’t compete with food production like first-gen biofuels. SAF, due to its production process, usually consist of fewer molecule types and fewer impurities than fossil jet, which results in cleaner combustion, 50–70% fewer particulates, and in turn fewer heat-trapping contrails. Why are we not flying with 100% SAF yet? Two reasons: fuel composition requirements and cost. The fuel specification for Jet-A, ATSM D-7566, currently requires 50% petroleum-derived fuels to ensure sufficient aromatics in the blend to preserve engine seals. Many forms of SAF don’t have sufficient aromatic compounds, which can cause seal shrinkage. Some companies, like Byogy, have addressed the problem of the aromatics content, so the specification could be amended once adequate experience shows that the fuels perform similarly. Regarding the economics, SAF is currently more expensive than fossil jet fuel for a few reasons:

|

AuthorMerlin is a pilot, cyclist, environmentalist, and product manager. Archives

June 2021

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed