|

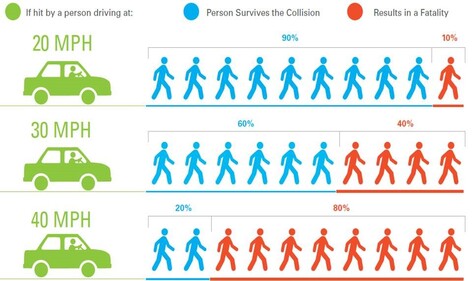

Have you ever gone through a city and asked yourself “Who the hell designed this, and what were they thinking??” I have this thought all the time while cycling around the Seattle area, and often can’t help wondering, “Has anybody involved in planning or building bike infrastructure ever actually ridden a bike on said infrastructure?” The answer in many cases must either be “No” or “They must have a death wish.” Look at this gem: The bike lane goes all the way up to the light and has two bikes stenciled onto it, which clearly means they intend cyclists to be there. On the opposite side of the intersection, there’s an ambiguous shoulder lane that just sort of tapers off on a 6% climb. Meanwhile, the speed limit sign in the distance reads 35 MPH (56 km/h), which means that people in cars are likely going at least 40 MPH (64 km/h). A moderately healthy cyclist climbs a grade like that around 10 MPH (16 km/h), which means the closing speed between car and bike are around 30 MPH (48 km/h) as the cyclist is unceremoniously forced into the “general purpose” lane where most motorists are not looking for them. This is a recipe for disaster, as getting run over at that speed is usually fatal, as seen in several studies and infographics: Vehicular energy goes up as the square of the speed, so anybody on foot, on a bike, or in a wheelchair will have bad chances in such a collision. This makes you wonder what the discussion in the traffic planning department actually looked like when they designed this mess. “Say, Randy, what should we do about the bike lane on the other side of that intersection? Should we continue it?” “Don’t know, Craig. The bridge tapers ahead, so we got a constraint, maybe the cyclists will just levitate to the other side of it.” “Brilliant, why didn’t I think of that? I was thinking of making trade-offs like merging the GP lanes to keep the bike lane, but levitation is much better.” “Yeah, we’ll save half a bucket of paint and a few posts by not restriping that. Sure a few cyclists unpracticed in levitation might get flattened, but the EMTs need practice using their spatulas to clean them up.” “Sweet, let’s go to happy hour.” The reason we end up with such bad infrastructure is that Randy and Craig don’t have a reason to care about what they’re doing. To be fair, they likely face a thicket of red tape and competing departments that won’t give them half a bucket of paint and a night to slap it on the road. Maybe the cone-laying union is on strike as well, who knows. How do we fix this? The solution to shoddy infrastructure is for cities to start dogfooding it: if Randy and Craig experienced the terror of merging their bikes in car traffic on that climb, they’d figure out a better solution faster. On their other rides around town, they’d start finding all the other death traps, like bike lanes in the door zone, tram tracks, and bomb-crater sized potholes on neighborhood greenways. They might look at their city’s budget and conclude that the Vision Zero project allocates more coin to its website than real improvements. In many of these situations, it’s more of a priorities problem than a money problem. Within the first few weeks of the dogfooding initiative, Randy and Craig would experience firsthand where the most urgent problems are, and then work out how to address them. They might have a bit of a budget for speed bumps and signs on a neighborhood greenway, but, having ridden on it, decide that they should skip the signs in favor of spending that money on filling the bomb craters because that’s a greater help to making it safe and usable within their budget. They could likewise use budgets more prudently by alpha testing ideas with temporary solutions like toilet plungers and biodegradable paint, then getting a group of beta testers from the local community to play with it and provide real user feedback, instead of wasting millions on yet another ineffective design. Infrastructure issues are not exclusive to cycling, though that’s where I personally see it the most. Sidewalks could be made a lot more useful with dogfooding as well. Here’s a wonderful specimen of a root bulge in a sidewalk: The ADA spec calls for an 8.33% gradient for curb cuts for navigability, presumably because anything steeper is hard or impossible to climb. This bulge looks a wee bit steeper than that, not to mention the lateral unevenness. If Wilma’s in charge of sidewalks and is required to dogfood it in a wheelchair, this would become a higher priority. She might see the well-paved strip on the other side of the green and ask these types of questions:

Through dogfooding, infrastructure teams will form better empathy for vulnerable road users, and will become better internal change agents. If those they report to remain unconvinced of the new proposals, they should implement “Skeptics Day,” where the dogfooders can invite any city leader for a day out on the “need fixing” roads or sidewalks. If higher ups experience the misery themselves with the cameras rolling, it will be harder for them to retreat into their offices and ignore the problem. If they do try to duck their responsibilities, maybe Randy, Craig, and Wilma could make a solid case for that person's salary to be reallocated to something useful. Where do we go next? The examples here are Seattle-centric, but the problems and lessons apply to plenty of other places as well. If you want to introduce this in your area, get involved with your local cycling/walking/wheelchair advocacy groups, see what they’re doing, and pitch the idea of putting infrastructure dogfooding on an initiative in a local election. Voters across the political spectrum in many places think that infrastructure is shoddy, so the idea of focusing their city’s attention and having their leaders put skin in the game should be broadly appealing. If you’re in infrastructure planning and want ideas on where to find high-ROI areas to address, check out the Strava Global Heatmap for pointers on where heavy bike and foot traffic are, then do a segment search on keywords like “death trap” and overlay those with the high traffic areas to find some areas to put near the top of your list. Lastly, form a user group of locals to give feedback. The fact that someone will finally listen and commit to doing anything should energize locals to provide more than enough actionable feedback.

0 Comments

|

AuthorMerlin is a pilot, cyclist, environmentalist, and product manager. Archives

June 2021

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed